Vol. 16 (2)

2017

Authors:

Soo-Kwang Oh. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5873-562X

Justin Hudson. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2419-5338

Artícle

Framing and reframing the 1992 LA Riots: A study of minority issues framing by the Los Angeles Times and its readers

1. Introduction

In the United States alone, racial tension has become an important topic in the news—scores of cases involving racial profiling, police brutality and social movements have sprung up as a key issue in society (Blay, 2017). Such issues have also become a staple in the rest of the world, with immigration and refugee issues disrupting nation states in Europe and elsewhere globally (Teitelbaum, 2017). One of the problems associated with such issues is media coverage (HQR, 2017). How do news media cover and frame issues that signify racial conflict and tension among ethnic minorities in their audiences? Furthermore, how do the affected minorities respond to the coverage, and does this response influence how the news media further frame the issue? In the wake of the social tension resulting from various incidents involving minority groups, the researchers sought to better address the questions above by examining a prominent case from the past, the 1992 Los Angeles Riots. We believe doing so will shed light on the context and history regarding how media initially frame minority-related issues and how they those frames shift when media are faced with active audience discourse.

News media provide coverage of newsworthy issues and fosters people’s participation in discussions that are significant for society (Domingo, 2011). However, this process may become problematic with the prominence or “mainstream-ness” of news media because mainstream media holds dominance in framing of news stories, determining how issues are understood by their audiences (Reese, Gandy, & Grant, 2001; Tewksbury & Scheufele, 2009). Potentially the mainstream news media could overlook important aspects of an issue, namely minority-related discussions. This could be detrimental to the ideal functioning of news discourse if affected parties in society are not adequately represented in the news media’s framing.

In this light, this study investigated whether reader discourse (in the form of letters to the editor) about the 1992 LA Riots framed the event differently in comparison to the mainstream newspaper, LA Times. Furthermore, we examined whether the mainstream news media changed its coverage of the riots six months after, and whether these changes correlated with the differences between reader discourse and original coverage.

2. Literature review

Journalism, public sphere, and minority representation

Journalistic processes allow news media and their readers to play a significant role for democracies. For a theoretical framework that puts this in perspective, this study takes a new approach that applies the notion of Habermasian public sphere (Habermas, 1989). The public sphere is a desired state of social life where public opinion can be formed through free participation and deliberation to aid the development of democracies. Participants communicate by using language to reach a mutual understanding and coordinate their actions. Journalism and its coverage of news initiate these communicative actions by providing a shared container of information and giving people a say by accommodating conversations (Zelizer, 2005). That is, development toward a desired public sphere may be aided by journalism with its information dissemination, representation and deliberation functions (Curran, 2005). Of these functions, representation is arguably most integral to the public sphere because its institutional categories require the following: 1) that there be a domain of common concern where each citizen and idea are represented, 2) inclusivity for any member of society to join the discussion, and 3) disregard of status, where it is devoid of pre-discriminating factors about a person’s characteristics (e.g., race, gender, socioeconomic status, etc.) (Bastos, 2011; Dahlgren & Sparks, 1991; Habermas, 1989; Holub, 1991).

However, in the mass communication model, representations of all ideas by members were not sufficient. People’s engagement with news did not really reach a sufficient state of deliberation because of the dominance of mainstream media’s interpretation of the story (Lambeth, 1998). People’s access to news-related communicative actions were limited. This was especially true for minority groups (McNair, 2000). The news media were in control—their decisions about newsworthy topics and what to think about (Valenzuela & McCombs, 2008), or how to think about those issues (Entman, 1993) were dominant themes for how news topics were interpreted and discussed. These dominating news media were called ‘mainstream’ media—one that dictates societal understanding and public opinion of news issues (Gunnell, 2011). If the mainstream media failed to recognize voices from minority groups, representation of these groups could never really be implemented.

Reader engagement with news as a way of representing the minority-related issues

In response to problems of representation in mainstream news media, readers have found a way to engage with news to make their voices heard. Engagement is a term that can cover an array of meanings when it comes to what types of actions can be called as such. For this study, reader engagement is defined as the “behavioral responses that result in tangible material in the process of mass communication” (Papacharissi, 2009, p. 30). Mass communication, unlike interpersonal or group communication, refers to a level of communication where the sender of the message does not know who one’s audiences are, but the audience is aware of where the message is coming from (McQuail, 2010), which makes it possible for audience engagement (as conceptualized above) to occur by means of providing feedback.

Furthermore, it is understood that evidences of news engagement will result in tangible mediated content that appears in the form of text, which is then shared by an unspecified readers, (Hargittai & Hsieh, 2010; Harper, 1998; Herbert, 2000). Such textual discourse from the reader usually shares the domain with the news media; often, the news media provides these forums for reader discourse in the form of letters to the editor or other forms of commentary (callers, panel members, columns, etc.). For this study, letters to the editor published in the mainstream newspaper was used.

These visible forms of reader engagement demonstrated an empowerment of citizens. They were able to reframe news discussions (Hermida, 2011), influence agenda-setting and gatekeeping decisions of news media (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009), and also direct other citizens toward useful information (Bruns, 2005). Potentially, as readers are able to provide a wider array of news frames for discussion, topics that may have been overlooked by the mainstream media such as minority-related issues can be shared and deliberated upon. Moreover, these newly employed frames from readers could be recognized by the mainstream news media, initiating a process through which reader discourse enhance the quality of news-related discussions in the public sphere.

This study focuses specifically on how the minority-related issues were framed by the mainstream newspaper and its readers during the 1992 LA Riots. As discussed in the following, Koreans and blacks as minority groups were significantly associated with the riots.

Mainstream media's framing of minority groups: Korean Americans and blacks

According to Chang and Diaz-Veizades (1999), the concerns of Asian Americans have traditionally not been covered by the mainstream media. Issues facing Koreans, for example, were rarely discussed by the LA Times and Los Angeles television networks before April 1992. When Korean Americans were discussed in the mainstream media, they were often praised as being a model minority group which were able to obtain success as in American society despite having recently immigrated to the nation (Chang & Diaz-Veizades, 1999; Cheung, 2005; Cho, 1993; Kim, 2012). Though seemingly complimentary, the model minority narrative was created by opponents of the Civil Rights Movement to discredit calls for government assistance to blacks and other minorities. Neoconservative commentators could point to Koreans and other Asians who have overcame racism while critiquing other minorities who clung to the lower rungs of society (Kim, 2012).

The “model minority” narrative put Koreans directly at odds with an African American population that became increasingly stigmatized in the years before the 1992 riots. By the 1980s and early 1990s, crime rose in black inner-city neighborhoods as these neighborhoods suffered from the effects of deindustrialization and social isolation caused by the flight of black and white middle-class residents (Kennedy, 2000; Wilson, 2005). In Los Angeles, as in other American urban centers, the vacuum created by the loss of industrial jobs was filled by a lucrative crack cocaine drug trade run by African American gangs (M. Davis, 1990). As South Los Angeles and other black neighborhoods in the United States saw a large increase in violence, black inner cities became symbolic of American societal decline and an increasing American fear of crime (Beauregard, 2003; M. Davis, 1990; Kennedy, 2000; Macek, 2006; Wilson, 2005). The mainstream media and even the ethnic press began to reflect this anxiety over blacks and their neighborhoods. In his study of coverage of black violence during this period, Wilson (2005) found that both conservative and liberal publications, including black newspapers, constructed the image of the pathological, out-of-control black male. Macek (2006) noted that a large range of media sources, from network television news shows to movies to advertising, reflected the national anxiety over black neighborhoods. Similarly, Davis (1990) noted a number of movies centered in Los Angeles, most notably the 1988 gang film “Colors,” focused on the out-of-control, crime-ridden city. According to Macek (2006), the moral panic created over the fear of black crime helped to sanction the Reagan and Bush administration’s law and order drug policies which focused on incarcerating black men instead of addressing the root causes of black discontent.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, a growing Korean-African American divide emerged in a number of American cities as Korean grocery store owners found themselves in a number of conflicts with the black communities in which they operated. The mainstream press and black press often exacerbated these tensions in a variety of ways. For example, during a 1990 black boycott of Korean stores in New York City, the New York Times and other New York media outlets took the side of the Korean store owners, who they believed were unfairly targeted by the black community. By focusing on the self-sufficiency and work ethic of Korean storeowners, the Times and other outlets promoted the idea of Koreans as a model for other minority groups, especially African Americans. Such antagonism on the part of the mainstream media helped to fuel antipathy between Blacks and Koreans (Chang & Diaz-Veizades, 1999). Resentment toward Koreans could be seen in a range of black media outlets. Korean store owners were often portrayed as impolite and racist exploiting black communities in black film and rap music (Kim, 2012). Black newspapers such as the Los Angeles Sentinel also routinely portrayed Korean store owners as exploiters and suggested a link between Koreans and the federal government in marginalizing the black community (Chang & Diaz-Veizades, 1999).

The case under study: The 1992 LA Riots and its coverage

To better understand the nature of mainstream news coverage and society’s engagement with such coverage, this research selected the 1992 LA Riots for the study. In detail, the case was examined in light of mass communication-minority community relationships in the mainstream media (LA Times) discourse and reader discourse (letters to the editor, called Letters to the Times).

While this event encompassed several communities and had multiple minority-related facets (Martinez, 1997), the study looked at audience engagement from a majorly affected demographic in the LA area at the time: the Korean immigrant community and the black community. As it is generally known, the LA Riots were sparked from the Rodney King case of 1991, where four police officers brutally beat King after a speed chase. All of this was caught on tape and the public condemned the officers, demanding a trial. When the trial eventually took place, all four officers were acquitted of any charges on the beating. This resulted in a six-day civil unrest from mostly African-Americans that resulted in 52 deaths, 2,239 injured and $1 billion in property damages (W. Davis, 1993; Kwon & Lee, 2009).

However, while the origin of anger was due to a racial problem that broke out from the King case, a major part of the rioting attacks was targeted toward Korean shop owners in the area. This was because of a growing hatred of the Korean American businesses in the black community as a result of the death of Latasha Harlins at a Korean-owned store that occurred less than two weeks after the King beating. Sunja Du, the storeowner, thought that the 15-year-old Harlins was shoplifting; they got into an argument and following aggressive utterances from Harlins. Du pulled the gun she kept under her counter and shot and killed Harlins. Later that year on November 11, 1991, Du received a relatively light sentence as the presiding judge at the time, Joyce Karlin, ruled that it was a voluntary manslaughter case (Stevenson, 2004). As collective anger associated with racial issues at its peak, the King verdict fueled anger that resulted in the civil unrest; however, it is also noted that right after the acquittal of officers involved with the King beating, KABC, the local TV network in the Los Angeles Area, showed the year-old footage of Harlins being shot by Du more than ten times alongside the Rodney King video, aiding the arousal of anger among the African Americans (Kwon & Lee, 2009). Moreover, many Koreans conducted business in the neighborhoods where initial attacks begun because Koreatown was located adjacent to predominantly black neighborhoods. However, the Koreans had not made much effort to “blend in” with the rest of the community, which gave neighbors a negative notion about the immigrant group (Hu, 1992).

As a result, Korean-owned shops were main targets for the attacks, and Korean shopkeepers armed with guns to protect their property. Notably, Edward Song, a Korean teenager, was killed in open gunfight, and a dominant percentage of the property damages from the riots were in the Korean shops (Kwon & Lee, 2009). The Korean American society as a potentially engaging audience had reasons to engage with the news because the Korean community may have felt a sense of emergency as their businesses were being attacked. It was the assumption that the group, or members of the group would turn to news outlets to have their voices heard.

Of the news outlets in the area, The LA Times was chosen as material for research because of its prominence that may have a significant impact on the presumed influence of the publication. According to census data, the population of the Los Angeles metropolitan area was over 14 million, the city itself with 3.5 million. The LA Times in 1990 had a circulation of 1.22 million, which covers at least three times as many people considering that one household had one subscription (Sicha, 2009). The number of people affected by this publication was almost identical to the city population and close to a quarter of the metropolitan area. Deriving from the above theoretical frameworks, the LA Times was determined to be the most adequate mainstream publication to address the question because of its perceived reach and prominence for all demographics in the area.

3. Research Questions

RQ1: How did the mainstream newspaper and its readers discuss minority-related issues differently before/during the 1992 LA Riots?

RQ2a: Was there a significant shift in mainstream newspaper’s framing of minority-related issues in subsequent series of articles remembering the 1992 LA Riots?

RQ2b: How does the shift in framing compare with the framing employed by the readers for general issues vs. minority-related issues?

The first research question aims to find whether there were discrepancies between the newspaper and its readers, especially with regard to minority-related issues, which is identified as a key component associated with the riots. Furthermore, with RQ2a and RQ2b this study seeks to address whether the mainstream newspaper paid attention to salient frames employed by its readers when publishing a series of subsequent news stories remembering the event. Here, our theorization of reader-employed frames derived from the literature discussing reception positions upon which audiences’ meaning-making takes place (Gray, 1999; Hall, 2006; Livingstone, 1991; Morley, 1980, 1992). That is, we argue that audiences recognize the media’s frames and interject with their own knowledge and perspective (Hermida, Fletcher, Korell, & Logan, 2012; Van Dijk, 1991; Worsley, 2010), which is understood in this study and its analysis as “reframing.”

4. Method

To address the research questions, this study employed a quantitative content analysis (Riffe, Lacy, & Fico, 1998) to analyze news stories from the mainstream newspaper (LA Times) and letters to the editor from readers (Letters to the Times) in light of how the LA Riots were discussed. The unit of analysis was each news story or letter, drawn from four significant time periods associated with the riots: 1) March 17th to April 16th, 1991, representing one month after the Rodney King beating and the Latasha Harlins shooting, which occurred at around the same time; 2) November 15th to December 14th, 1991, which is the month after the sentencing of Sunja Du regarding the Harlins case. Du’s receiving a light sentence brought forth discussions regarding two minority groups involved (Koreans and blacks), leading the researchers to believe it was a significant time period building up to the actual Riots happening five months later; 3) April 30th to May 29th, 1992, the month from the start date of the 1992 Riots, which broke out on April 29, 1992 after people found out about the acquittal of the four police officers involved in the beating of Rodney King; and 4) October 29th to November 28th, 1992, which was six months after the breakout of the riots. LA Times published a series of articles discussing different aspects of the riots.

Furthermore, the first, second and third timeframes were grouped as “before/during the riots” and the fourth timeframe was labeled as “after the riots”. Such groupings of news articles were useful for this study because it was aimed at comparing salient themes of discussion used by the mainstream newspaper when remembering an event after a certain time. This fourth time period was used to only collect LA Times’ news stories. Letters were collected only for the “before/during” time periods because we assumed that readers would not write letters to the editor about the riots six months after the riots had happened. However, the LA Times did publish a series of news stories remembering the riots after six months as part of an agenda-setting decision of the mainstream newspaper. In other words, reader discourse regarding the riots would not have been salient enough at this point in time. Moreover, the study was aimed at understanding how letters written before/during the riots may have influenced how the mainstream newspaper remembered the riots in its subsequent series of news stories. Thus, there was not a search for letters written in the last time period.

Coding results of news stories and letters from each time period (before/during and after) and material type (news stories vs. letters) were then analyzed and compared.

Sample

The total number of news stories (N=150) was determined by searching the ProQuest database. Due to the main news topic inherent in each significant time period, different search terms were used. For the first two time periods (March/April 1991 and November/December 1991), search terms “Rodney King” OR “Latasha Harlins” were used, yielding a result of 55 unique news stories for the first time period and 41 for the second time period. After filtering the results by relevance, the first 25 news stories from each time period were collected. For the third time period (April/May 1992), the search term “riots” was used, resulting in 621 news stories. When these results were also filtered by relevance, it was found that the search term included many less relevant news stories, decreasing the number of highly relevant stories to 133. Accordingly, the first 50 news stories (filtered by relevance) were collected. For the last time period (October/November 1992), it was identified that the LA Times used the header “Understanding the riots – Six months later” for the series of news stories written about the riots. Therefore, the same header was used as the search term, garnering a search result of 76 unique news stories. After filtering the results by relevance, the first fifty news stories were collected. As a result, 100 news stories were collected for before/during the riots and 50 stories were collected for subsequent stories after the riots.

Due to the total number of search results by material type (news stories vs. letters), a different sampling strategy was used to determine the sample size for the letters. The total number of letters written by readers (N=200) was determined from microform data of the print version of the LA Times for each time period. Because letters are usually shorter in nature and limited to one or two discussion themes per letter, the proportion of letters collected from the population was larger. It was found that for the first two time periods, 39 of 309 and 22 of 297 letters, respectively, were related to King and/or Harlins. For the third time period, 156 of 327 letters discussed the riots. As a result, it was shown that 217 of 993 letters were associated with riots-related themes. Of the 217 letters, seventeen letters that were two sentences or shorter were discarded because they were deemed to be less useful for coding purposes. Consequently, 200 letters from the before/during the riots group were selected. See the table below for a summary of the sampling process.

Table 1. Numbers and figures of sampling procedure

|

Before/During the riots |

After the riots |

Total |

||

3/17/91 – 4/16/91 |

11/15/91 – 12/14/91 |

4/30/92 – 5/29/92 |

10/29/92 – 11/28/92 |

||

Search term(s) used

|

“Rodney King” OR “Latasha Harlins” |

“Rodney King” OR “Latasha Harlins” |

“Riots” |

“Understanding the Riots – Six months later” |

|

Total # of unique news stories searched |

55 |

41 |

133 |

76 |

305 |

Total # of news stories selected |

25 |

25 |

50 |

50 |

150 |

Total # of letters |

309 |

297 |

327 |

-- |

993 |

Total # of letters related to riots |

39 |

22 |

156 |

-- |

217 |

Total # of letters discarded due to length |

3 |

3 |

11 |

-- |

17 |

Coding

As mentioned above, each news story or letter was the unit of analysis. A coding sheet was generated by constructing categories for analysis that exclusively and exhaustively cover (Neuendorf, 2002) the concepts set forth in the research questions. The type of source (news story or letter) and time period (before/during the riots, after the riots) were coded, followed by category systems developed with theoretical considerations for framing analysis.

In order to understand what salient frames were inherent in the material, the coding sheet included different aspects of the riots that were used as frames. Here, the coding categories focused on framing as a process whereby communicators construct perspectives that allows for a given situation to be interpreted in a particular way (Entman, 1991, 1993; Goffman, 1974). Frames operate by providing a narrative account of an issue or event and highlighting a specific point of view (Gamson, 1992; Reese et al., 2001). The act of selecting and highlighting perspectives from the issue results in the communicator gaining power dominance through priming and agenda setting that are achieved through successful framing (Entman, 2007). In other words, framing works as the process and tool through which the communicator promotes wanted agendas.

In this sense, Kuypers (2009) notes, frames are “powerful rhetorical entities that induce us to filter our perceptions of the world in particular ways, essentially making some aspects of our multi-dimensional reality more noticeable than other aspects” (p. 181). When analyzing how these accounts are presented, the communicator’s (commenter’s) acts of encouraging, promoting or convincing receivers of the interpretive frames result in selectively emphasizing ideas that have potential to mobilize public opinion and engage others in dialogue by offering themes that could be agreed upon (Jerit, 2008). As such, this approach to analysis looks at the material “for what it potentially does than for what it is” (Corbett, 1969, p. xii). Key categories were as follows:

1) General frames of discussion

Damages/disruption referred to mentioning casualties, monetary damages, etc.; Causes/explanation was when the discussion was focused on providing context about why the riots (or events leading up to the riots) occurred; Public safety included frames about the dangers of the city. Other categories such as Police reaction and legal issues were added due to the criminal nature of the events associated with the riots. Finally, City reconstruction referred to discussions framed toward recovering from the riots.

2) Race and minority-related issues

Going into the specific research questions the coding sheet included various categories about how the minority-related issues were discussed. Categories were based on whether issues such as racism, strife (toward and among minority groups) and reconciliation were mentioned in the news story or letter (West, 2016). In addition, each unit of analysis was code for whether the King or Harlins case was mentioned, which were both minority-related issues.

Moreover, the coding sheet included how each severely affected minority group (Koreans and blacks) was discussed in the material: as victims, as the group to blame, their relationship with society and/or other groups, and characteristics of the group.

3) Mentioning the other source

Finally, the coding sheet included a category about whether each type of source (news story or letter) mentioned the other and how they evaluated the other source (none/neutral, positive, negative), if applicable. For instance, the researchers found a number of letters disagreeing with a specific news story, which were coded as “mentioning the other” and “negatively evaluating the other”. For a list of categories for analysis, please refer to the coding sheet in the appendix.

Intercoder Reliability

After a coder training session and establishing consensus on the definitions of each category, the two coders independently analyzed twenty percent of the total sample of 350 news stories/letters. Comparison of the two coders’ agreement of 70 news stories/letters (randomly selected) yielded a Krippendorf’s Alpha of .88. Highest Kalpha was with ‘mention of the other’ = .93 and the lowest value was with ‘strife’ = .84. After the intercoder reliability from the initial sample was calculated, the coders compared and discussed results and reached an agreement on discrepancies and future coding decisions. Then each coder analyzed half of the remaining 280 news stories/letters.

5. Results

Framing the LA Riots (General)

To investigate whether news stories and letters differed in terms of the general frames of discussion, chi-square tests were conducted on coding decisions regarding each material type before/during the riots. Statistical significance of p<.05 was used.

Table 2. Cross-tabulation of general frames in news stories published before/during the riots and letters from readers

Frame Categories |

Material Type |

|

|

|

|

News Stories Before/During (N=100) |

Letters Before/During (N=200) |

χ² |

df |

Damages/Disruption |

47.0 |

45.0 |

.107 |

1 |

Causes/Explanation |

21.0 |

62.0 |

44.877*** |

1 |

Public Safety |

29.0 |

60.5 |

26.460*** |

1 |

Police Reaction |

39.0 |

37.5 |

.064 |

1 |

Legal Issues |

46.0 |

33.0 |

4.816 |

1 |

Politics/Elections |

25.0 |

25.5 |

.009 |

1 |

City Reconstruction |

22.0 |

25.5 |

.444 |

1 |

Note: values are in frequency terms (percentages); * =p< .05, ** =p<.01, *** =p<.001, |

||||

Table 2 indicates that usage of general news frames did not differ significantly across material type in the before/during time period. Significance in difference among these frames was shown for ‘causes/explanation’ (χ² (2) = 44.877, p<.001) and ‘public safety’ (χ² (2) = 26.460, p<.001). More specifically, both frame categories were significantly more frequently used in the letters than for news stories published before/during the riots.

In order to understand how the framing changes in subsequent news stories were correlated to the differences shown from the letters, researchers performed another chi-square test for frequencies of frame categories between news stories written before/during and after the riots. By so doing, when significant differences were identified in the first chi-square test of news stories before/during and letters, the researchers further examined whether there were significant differences for the subsequent articles for the same frame category. Frame categories showing a significant difference of frequencies for both chi-square tests indicated that the changes in framing in subsequent news stories may be correlated with the differences of letters from news stories published before/during the riots. In other words, the researchers only identified frame categories that showed significant differences in both tests as potential frames that indicate a correlation between the letters and subsequent news stories.

Table 3. Cross-tabulation of general frames used in news stories before/during and subsequent news stories

Frame Categories |

Material Type |

|

|

|

|

News Stories Before/During (N=100) |

Subsequent News Stories (N=50) |

χ² |

df |

Damages/Disruption |

47.0 |

72.0 |

8.429** |

1 |

Causes/Explanation |

21.0 |

56.0 |

18.564*** |

1 |

Public Safety |

29.0 |

62.0 |

15.125*** |

1 |

Police Reaction |

39.0 |

28.0 |

1.765 |

1 |

Legal Issues |

46.0 |

12.0 |

17.013*** |

1 |

Politics/Elections |

25.0 |

6.0 |

7.926** |

1 |

City Reconstruction |

22.0 |

54.0 |

15.518*** |

1 |

Note: values are in frequency terms (percentages); * =p< .05, ** =p<.01, *** =p<.001, |

||||

As shown in the table, all frame categories with the exception of ‘police reaction’ were significantly different for news stories published in the two time periods. Of these, the two frame categories that were significantly different in the first chi-square test (causes/explanation and public safety) were compared in terms of directions of changes.

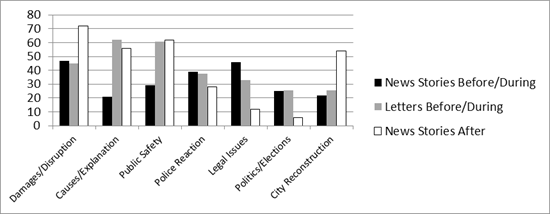

Chart 1. Frequencies of frames by material type/time period

The chart above illustrates differences in frequency of frames appearing in each material type/time period. As shown in the chart, the directions of changes from the news stories before/during period increased consistently with letters and subsequent stories for ‘causes/explanation’ and ‘public safety.’ Thus, while one cannot conclude on causality, a correlation was found for these two categories where framing changes in subsequent news stories were more closely correlated to the differences shown from the letters. Reversely, it was also found that there was no correlation for other categories showing significant differences for news stories by time period.

Framing the LA Riots (Minority-related issues)

To address the research questions in detail, the coding sheet included categories pertaining specifically to minority-related issues. The same procedure of chi-square tests was performed to investigate the differences regarding frequencies of minority-related frames for each material type and time period.

Table 4. Cross-tabulation of minority-related frames in news stories published before/during the riots and letters from readers

Minority-related frames |

Material Type |

|

|

|

|

News Stories Before/During (N=100) |

Letters Before/During (N=200) |

χ² |

df |

King/Harlins |

79.0 |

63.5 |

7.444** |

1 |

Racism |

36.0 |

56.5 |

11.207** |

1 |

Strife |

62.0 |

65.0 |

.260 |

1 |

Reconciliation |

21.0 |

38.5 |

9.282** |

1 |

Koreans (victims) |

28.0 |

13.0 |

10.163** |

1 |

Koreans (blame) |

25.0 |

13.5 |

6.153* |

1 |

Koreans (relationship) |

26.0 |

12.0 |

9.408** |

1 |

Koreans (characteristics) |

9.0 |

11.5 |

.437 |

1 |

Blacks (victims) |

55.0 |

55.0 |

.000 |

1 |

Blacks (blame) |

24.0 |

17.5 |

1.783 |

1 |

Blacks (relationship) |

36.0 |

28.0 |

2.007 |

1 |

Blacks (characteristics) |

14.0 |

13.0 |

.058 |

1 |

Note: values are in frequency terms (percentages); * =p< .05, ** =p<.01, *** =p<.001, |

||||

Table 4 indicates that usage of minority-related frames differed significantly across material type and time period. Significance in difference among these frames were shown in the order of ‘racism’ (χ² (2) = 11.207, p<.01), ‘Koreans (victims)’ (χ² (2) = 10.163, p<.01), ‘Koreans (relationship)’ (χ² (2) = 9.408, p<.01), ‘reconciliation’ (χ² (2) = 9.282, p<.01), ‘King/Harlins’ (χ² (2) = 7.444, p<.01), and ‘Koreans (blame)’ (χ² (2) = 6.153, p<.05). More specifically, letters showed higher frequencies only for ‘racism’ and ‘reconciliation’. Moreover, no significant difference was found for frames regarding blacks. It is also worthy of note that differences for strife among minority groups were not significant.

The same analysis of frequencies was performed to identify frames that saw significant changes for both tests.

Table 5. Cross-tabulation of minority-related frames in news stories published before/during the riots and subsequent news stories

Minority-related frames |

Material Type |

|

|

|

|

News Stories Before/During (N=100) |

Subsequent News Stories (N=50) |

χ² |

df |

King/Harlins |

79.0 |

40.0 |

22.594*** |

1 |

Racism |

36.0 |

56.0 |

5.451* |

1 |

Strife |

62.0 |

54.0 |

.884 |

1 |

Reconciliation |

21.0 |

46.0 |

10.050** |

1 |

Koreans (victims) |

28.0 |

28.0 |

.000 |

1 |

Koreans (blame) |

25.0 |

6.5 |

7.926** |

1 |

Koreans (relationship) |

26.0 |

28.0 |

.068 |

1 |

Koreans (characteristics) |

9.0 |

28.0 |

9.269** |

1 |

Blacks (victims) |

55.0 |

32.0 |

7.073** |

1 |

Blacks (blame) |

24.0 |

34.0 |

1.678 |

1 |

Blacks (relationship) |

36.0 |

38.0 |

.057 |

1 |

Blacks (characteristics) |

14.0 |

38.0 |

22.594*** |

1 |

Note: values are in frequency terms (percentages); * =p< .05, ** =p<.01, *** =p<.001, |

||||

This table indicates that usage of minority-related frames differed significantly across time periods for news articles. When comparing the categories significant in the first chi-square test, the following categories were also significant: ‘King/Harlins’ (χ² (2) = 22.594, p<.001), ‘racism’ (χ² (2) = 5.451, p<.05), ‘reconciliation’ (χ² (2) = 10.050, p<.01), and ‘Koreans (blame)’ (χ² (2) = 7.926, p<.01). More specifically, subsequent news stories also showed higher frequencies only for ‘racism’ and ‘reconciliation’. However, it is also worthy of note that more categories were significantly different for this comparison (news stories over time) than for the first comparison (news stories vs. letters).

The direction of frequency changes from the two chi-square tests were also compared, using the following chart shows a bar graph of frequencies by material type and time period.

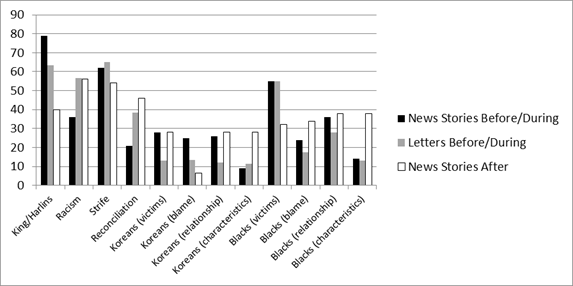

Chart 2. Frequencies of minority-related frames by material type/time period

As illustrated in the chart and also through a comparison of chi-square tests, salient differences in frequencies between news stories (before/during) and letters/subsequent stories were noted for ‘racism’, ‘reconciliation’, ‘King/Harlins’, and ‘Koreans (blame)’. In other words, it was found that differences in frequencies between news stories of the two time periods were correlated with the differences between the number of news stories before/during and the letters.

Reference to other

Finally, frequencies of each material type referring to the other were compared. As can be seen in the table below, there were no cases of news stories mentioning reader discourse as the source of the story, whereas 46% of the letters referred to the story.

Table 6. Cross-tabulation of reference to the other

Reference to the other |

Material Type |

|

|

||

|

News Stories (N=150) |

Letters (N=200) |

χ² |

df |

|

Reference to the other |

0 |

46.0 |

93.605*** |

1 |

|

Evaluation of the other (negative) |

0 |

13.5 |

53.222*** |

2 |

|

Evaluation of the other (positive) |

0 |

16.0 |

56.248*** |

2 |

|

Note: values are in frequency terms (percentages); *** =p<.001, |

|||||

6. Discussion & Conclusion

The overarching research question was: How did the mainstream newspaper (LA Times news stories) and its readers (Letters to the Times) discuss the 1992 LA Riots? As discussed above, the mainstream news organization holds dominance when it comes to framing decisions about a news topic (Entman, 1993). Potentially, the mainstream news organization may frame a topic that is different from how the readers (participants of the public sphere) view it. Therefore, a contradiction may occur where the mainstream newspaper provides a different frame than ones that are being employed by its very readers in the discussion forum provided by the newspaper.

Overall, it was found that there were differences in how the mainstream newspaper framed the 1992 LA Riots when compared to reader discourse with regard to ‘causes/explanation’ and ‘public safety’. The latter may be telling us that the mainstream newspaper’s representative frames differ from what the public understands to be the most salient issue regarding the news topic. Whereas readers continuously raised questions about public safety, the mainstream newspaper set the agenda with more technical frames such as legal issues or politics/elections. This may be due to the powers of professionalism (Doctor, 2010) and gatekeeping of news topics (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009) that blinds the mainstream media from paying close attention to the more severe issues being discussed by the public.

This point is further supported by the fact that ‘causes/explanation’ appeared nearly three times as much in reader discourse. While still conjecture, it may be that the mainstream newspaper was more occupied with providing a broad range of coverage it believes to be important (Valenzuela & McCombs, 2008) rather than utilizing time and space to provide context and explanation as to why such a tragic event occurred in our society.

On the other hand, results indicated that the LA Times changed its framing of the issue on all but one frame category when publishing a subsequent series of news stories remembering the riots. For instance, discussions regarding ‘legal issues’ or ‘politics/elections’ decreased dramatically, while frames of ‘damages/disruption’ and ‘city reconstruction’ increased in great deal. These are arguably news decisions regarding how to interpret the story so that it serves the public better (Haas, 2007; Haas & Steiner, 2003).

Moreover, among the frame categories that increased in frequency in subsequent news stories, the two categories that showed a discrepancy between the stories and letters (‘causes/explanation’ and ‘public safety’) were included. This indicates that the mainstream newspaper may indeed be paying attention to reader discourse, providing relevant coverage of those issues when it comes time to remember the event. This may have been even more convenient for the LA Times to do, because reader discourse was in the form of letters, which are read and selected by the editors in the newsroom. It may have been that the LA Times noticed a huge discrepancy between framing by the newspaper and its readers, thus making a decision to include those frames in subsequent news stories.

As the case under study was closely associated with minority groups, mainly Koreans and blacks, the study sought to address how minority-related issues were discussed differently. It was found that there was a significant difference in whether ‘King/Harlins,’ ‘Racism’ and ‘Reconciliation’ were discussed in news stories as opposed to the letters. More specifically, the ‘King/Harlins’ frame was used significantly more by the LA Times than by the readers. This may be because the mainstream newspaper took the initiative to make sense of the story. While not providing enough explanation about why the riots started (as found in the analysis of general frames), the mainstream newspaper utilized the two vividly remembered events to frame the issue. Such a finding may be explained through how the mainstream media looks for news events or spectacle (Edelman, 1988) that help signify an issue, so as to make the conveyance of preferred meaning (Carey, 1989) easier (Compton, 2004; Edelman, 1988). This is problematic for minority-related issues because the minority issue may get communicated to the public without proper deliberation of the characteristics of the group involved or their relationships within society. The Harlins shooting being mentioned alongside the acquitted police officers from the King beating led the blacks to direct their anger and frustration toward Koreans. As a result, some argue that the mainstream media of the LA region instigated the riots rather than providing coverage of the issue to inform citizens (Kwon & Lee, 2009).

Another emerging discussion from the differences in framing by the LA Times and its readers is about how there were significant differences in how Koreans were discussed, but not for blacks. It was found that almost all aspects of Koreans (as victims, as the group to blame, their relationships with others in society) were discussed more frequently by the mainstream newspaper. This may be attributed to the ‘model minority’ nature of Koreans and how this factor plays into participation in the public sphere. They have been known to be a reserved, model minority group that did not speak up as much toward social issues, and that has to do with certain traits of the group as a whole (Lee & Park, 2008; Park, 2010). As a result, readers from this group may have chosen not to cause controversy by participating in the discussion forum with one’s own ideas. This point is also supported by the fact that many letters from Koreans were highly defensive of the group itself. It could have been that such a characteristic (defensive as group, model minority) of the Koreans led the LA Times to reduce the discussions about how Koreans should be blamed for the riots. In fact, the frequency of such frames dropped significantly by close to 20%. In a study that content analyzed LA Times’ coverage of Korean Americans before and after the riots, it was also found that news stories after the riots ceased to frame Koreans in light of racial tensions, but more as minorities leading normal lives as fellow citizens (Ban & Adams, 1997).

On the contrary, it was found that frames regarding blacks were discussed just as much in reader discourse as were in the news stories. Perhaps this indicates that unlike Koreans, blacks as minorities had established a culture where its representation of voices in mainstream media was possible. It may be that blacks’ active efforts to be represented led the mainstream newspaper to pick up on the importance of covering blacks-related issues, such as characteristics of the group, which saw a 28% increase of subsequent story series.

Furthermore, it was found that when the LA Times published subsequent series of news stories about the riots, it significantly changed the frames of discussion regarding many minority-related issues. For instance, the ‘King/Harlins’ frame was reduced by almost half, whereas frames such as ‘racism’ and ‘reconciliation’ nearly doubled in terms of frequencies of appearance. The decrease in mentioning of King and/or Harlins may be the result of the LA Times paying attention to reader discourse about how it was constantly making such connections with the riots, when the larger issue was related to racism and minority-related issues in society. This plausible explanation shows the importance of reader discourse and public opinion regarding how the news event is reshaped in our memories. After all, journalism is there to aid the betterment of society; it will eventually pay attention to the framing of issues if it becomes salient enough in society (Benkler, 2006). It has been also been discussed that the riots was a significant event in that the journalists of mainstream media were determined to cover poverty, which is not usually a popular topic in mainstream news because advertisers were not keen on the topic (Rendall, 2007). Upon recognition of such issues for the advancement of society, it is possible that the mainstream newspaper also employed the frame of ‘reconciliation’ among and toward minority groups such as Koreans and blacks, as evidenced by more than a double increase in the subsequent series of news stories published about the riots.

It is also understood that this study is met with some limitations, namely the nature of letters to the editor as salient evidence of audience discourse. For letters, the mainstream newspaper always holds the decision power over what material gets published. Therefore, further study opportunities ought to identify various other means to collect empirical data of reader-initiated discussions. Furthermore, it would be worthwhile to gather empirical data consisting of firsthand accounts from persons involved in the riots. With rapid increase in reader discourse in other venues such as social media websites, comparing findings from primary sources with regard to the riots with audience discourse in contemporary cases could provide insight toward how relationships between the mainstream newspaper and its readers have changed in light of minority-related issues framing.

In conclusion, the findings indicated that the LA Times showed a larger discrepancy in comparison to its readers in framing of both general and minority-related issues. It was also found that discussion of minority-related frames significantly changed in a way that correlated with the framing by its readers. It is argued that such findings provide insight toward how the mainstream media deals with a minority-related topic in the early stages and eventually pays attention to reader discourse in order to provide the type of coverage in the future that best represents the public sphere, therefore providing service to the functioning of the public sphere. Findings from this study are of value to professionals and scholars alike—issues of minority-related coverage are crucial to an advancement of our democratic societies, something scholars strive to investigate and professionals to implement.

Furthermore, by understanding the nature and trends of mass media’s coverage of social issues and how their framing of issues changes according to reader/viewer discourse, it will provide insight toward how mass communication in the contemporary media landscape covers similar issues. Findings and takeaways from this study can be applied to current issues in society that saw mainstream media’s framing shift as a result of audiences’ active reframing. The researchers expect that such a phenomenon will be more salient in the age of interactive new and social media. Therefore, in the future the researchers seek to compare this case to more recent issues involving minority communities and mainstream media coverage. It will enable the researchers to garner a more comprehensive understanding of the issue that can be applied to the now and future of minorities coverage in mass communication.

References

Carey, J. (1989). Communication as culture: Essays on media and society. New York: Routledge.

Davis, M. (1990). City of quartz: Excavating the future in Los Angeles. London: Verson.

Davis, W. (1993). The untold story of the LA riot. U. S. News & World Report, 114(21), 34-47.

Doctor, K. (2010). Newsonomics. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Edelman, M. (1988). Constructing the political spectacle. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gamson, W. A. (1992). Talking Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holub, R. (1991). Jurgen Habermas: Critic in the public sphere. London: Routledge.

Hu, A. (1992). Us and them. The New Republic, 206(22), 12-14.

Kwon, H., & Lee, C. (2009). Korean American History. Los Angeles: Korean Education Center.

McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail's mass communication theory (6th ed.). New York: Sage.

Morley, D. (1980). The 'Nationwide' audience: Structure and decoding. London: BFI.

Morley, D. (1992). The 'Nationwide' audience: Structure and decoding. London: BFI.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rendall, S. (2007). A poverty of coverage. Extra!, 20, 8.

Shoemaker, P., & Vos, T. (2009). Gatekeeping theory. Routledge.

Worsley, S. M. (2010). Audience, agency and identity in Black popular culture. New York: Routledge.

APPENDIX: CODING SHEET

MATERIAL TYPE

- News Story / Letter

- Time Period

MENTIONING THE OTHER

- Reference to the other

- Evaluation of the other (None/Neutral, Negative, Positive)

GENERAL FRAMES OF DISCUSSION

- Damages/Disruption

- Causes/Explanation

- Public Safety

- Police Reaction

- Legal Issues

- Politics/Elections

- City Reconstruction

MINORITY-RELATED ISSUES

- Racism

- Strife

- Reconciliation

- King/Harlins

MINORITY GROUP: KOREANS

- Victims

- Blame

- Relationship with others/society

- Characteristics of group

MINORITY GROUPS: BLACKS

- Victims

- Blame

- Relationship with others/society

- Characteristics of group